Video Games as Story, and So Much More Than Story

I could probably define the eras of my life by video games. The vague memory of my parents informing me of their impending divorce has the Donkey Kong 64 pause music in the background. There were times my relationships with my sisters were defined by arguments over Mario Kart, and also times we would sit together and play songs from the Legend of Zelda games on the piano or the flute. In the second house I lived in, my mother and sisters would gather around which one of us was playing, and help to give advice on puzzles and possible solutions. And other times, alone at a young age, up later than I should have been, with the dark slowly encroaching on me, I would remember the eerie music of a video game dungeon haunting me as I insisted on just a few more minutes.

This is not just because video games happened to be present, but rather each game has come to define my life experiences. But why? Why do video games take up such a large part of my life? Maybe they were just fun experiences, happy moments remembered fondly. But maybe, they were a lot more. Maybe they were just as important as the stories I connected to in the books I read or the movies I watched.

Video games have provided me some all-important narratives, and I’m not alone. I don’t just remember pause music, or recall learning “the Song of Storms” on the recorder, but also think affectionately about the characters, the narratives, and the meaning behind a variety of symbols. Video games have provided stories and mechanisms to experience stories which have lingered with me for years and years after the first initial play.

Video games are a complicated medium for contemporary storytelling. They come in many different genres, have many different approaches, and can look massively different from game to game. Even the way people play games can differ. What the goals are - or even if there is a goal - isn’t universal. Despite this, video games are avenues of powerful storytelling in our contemporary age. They are just as important and prevalent as movies and television shows, and even books and plays.

Today, I want to ask a few important questions: How are video games like stories? And – perhaps more importantly - how are they so much more than stories?

Video Games as Storytelling

One of my earliest gaming experiences is on the computer, playing one of the many Kings Quest games. In these games, you play, typically, as Graham, a king who goes on a variety of adventures and quests. Perhaps the specific one was Kings Quest 5, where King Graham is on a walk through the countryside when an evil wizard appears and magically steals the whole castle. The player then has to lead Graham through a series of trials and puzzles to defeat the evil warlock and save his castle, and his family who was inside it.

For games like King’s Quest, the role of the narrative is a lot more obvious. It helps to give purpose for all the choices the player is making - otherwise, there would be no reason to guide King Graham anywhere, and no structure to provide puzzles and problem-solving scenarios to the player. Other games, however, may be less obvious. Tetris, for example, is not a straightforward narrative, so much so it is often classed in the categories of games which are narrative-less. The game focuses, instead, on the puzzle itself, and the need to best yourself and others as a compelling reason to keep going.

The combination of game and narrative inherent in video games created quite a rift in early academic studies. For these early days, the field was divided by the narratology/ludology debate. Essentially, scholars were divided into two camps: those who saw video games as stories - the narratologists - or those who thought of them as primarily games - the ludologists. The debate divided much of the scholarship, and academics were often forced to choose which side they believed most in before even starting the process of partaking in the research1.

In today’s discipline, this debate has been left on the lecture room floor with the bits of dried gum and lost notes. Most scholars in the study of video games see a marriage between these two elements. When I talk about how video games are stories, I do not want to lose a very important part of them - they are, in fact, still games.

In order to truly see how wonderfully complicated and nuanced video games can be, we have to continue to see it this way. They can’t be just games, or just narratives - what makes them amazing and interesting is that they are both.

Video games are primarily defined by their interactivity, and how one must play the game to get to the end of the story. If the player is not very good at the game, it can essentially lock them out of continuing the story. Not only this, but some games even rely on the player’s decisions and interactions to create the story for them.

Beacon Pines, for example, is a narrative-driven game. Developed by Hiding Spot Games and released in 2022, Beacon Pines follows Luka, a child in the town of Beacon Pines, who begins to uncover the mysterious secretes of his hometown. To “win” the game, the player must reach a happy ending to the story. There are many times in which the story comes to an end prematurely, or in an unsatisfactory way.

Throughout the game, the player is prompted to make decisions for Luka and his small gang of friends. These decisions lead to both successes and failures, depending on the choice, and the player must continue to navigate the various turns the story takes until they find the happy ending. This game mechanic is pushed by a visual representation of a book, which is being narrated out-loud to the player. Whenever a decision should be made, or an ending is reached, the player sees the book and the narrator makes a comment on whether it was a good ending or not. The player must then go back to a “turning point” in the story to try again with a different choice.

These kinds of narrative driven games demonstrate it isn’t just a straightforward linear narrative players engage with, but rather one which is determined by the player themselves. Not only does the player decide if the story continues, they even decide what form that story takes.

There are, obviously, some limitations on games like Beacon Pines. The player is not completely free to make any decision - they must follow the pre-set choices programmed into the game by the developers. It is important to note the player’s engagement with the game as a game is also necessary for the way the narrative is experienced. The two things are intricately linked together.

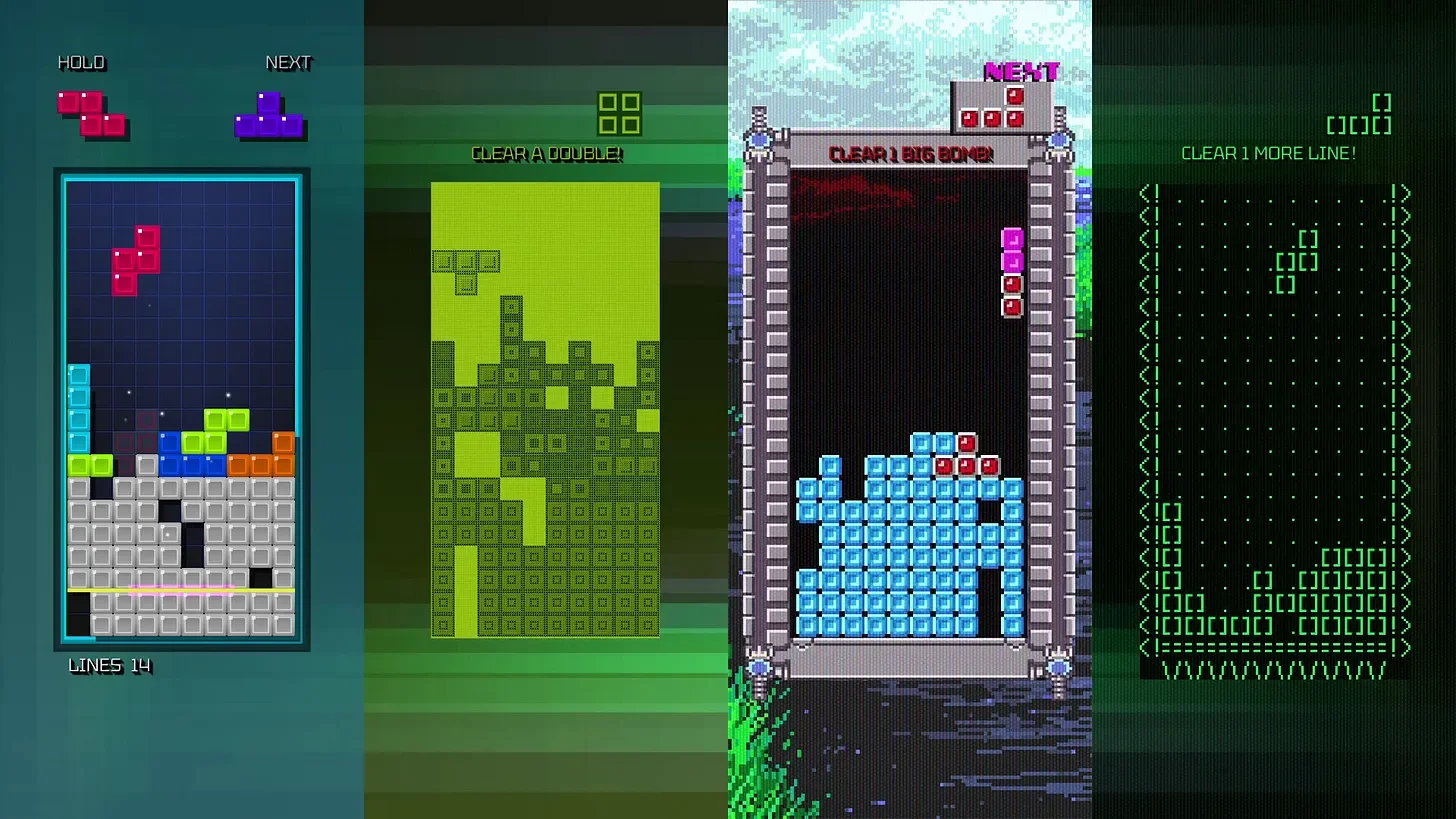

In fact, even games which seem more game than narrative can still have both of these aspects present. On its surface, Tetris is not a narrative game. It is a game focused on actual mechanics of playing and the player’s capabilities in puzzle solving. There is no story to unfold as players progress. Despite this, there are still aspects of narrative embedded in this form of game.

The first narrative is a simple one: what’s next? I play to find out what happens when I win, what happens if I keep going. How far can I keep going? Even though the question of what’s next isn’t a traditional idea of story, it’s still an important facet. Let me finish up this level so I can find out what happens next.

The second form of narrative present is in the individual story of success or failure which unfolds while playing the game. Like how sports competitions can carry an almost-storyline for fans to follow, so, too, can puzzle games. Near success being suddenly snatched away at the last minute by a poor decision or an unexpected turn can be just as exciting as a surprise twist on a narrative. Because it is a surprise twist to a narrative, just one which isn’t scripted. Likewise, sudden victory at the claws of inevitable defeat can be exciting and heart-pounding, and keep us playing more and more. It’s not just the gameplay which becomes addictive, but the storylines of our own successes and failures.

There’s a third type of story which can unfold from these kinds of games as well, one which I may explore in greater detail in a separate post. Tetris was created in 1985, and since has had many different variations and versions. Its import to the world of video games was cemented when it became one of the first games inducted into the World Video Game Hall of Fame in 2015. Tetris is a game which has so many different forms and variants, constnatly putting out new versions with new graphics on new consoles, always present in the lives of their players. After one release, my younger siblings who were probably only about ten at the time, were excited about it, and my whole family gathered to share stories of playing the original game on a large brick Gameboy. My father even dug out his old Gameboy to show them.

Tetris became, in this moment, a story uniting my family across several generations. My father’s love for Tetris came first, as it was his Gameboy we used to play on as kids. He taught us the game, competed with us, and we would regale each other with the stories of our successes or failures. Then, decades later when my younger siblings were born, they, too, became enmeshed in the story, and they soon began telling us of their games - their successes and failures - and we returned with reminiscences of our own.

Tetris, therefore, became a point of connection and love, a game and story shared with one another. Essentially, even when the game itself is not crafting a narrative players follow, a narrative is still being created. Our stories, the ones we create, becomes part of the narrative of the game because its inherently connected to our experiences of it. Therefore, our stories, the game’s stories, and the active playing of the game are all inherently linked together.

More Than Stories

“It really helped me reawaken my curiosity for the unknown and helped me come to terms with my fears of death and what might happen if everything I love is gone.”

This was written on a Reddit thread for the game Outer Wilds, an action-adventure game in which players are stuck in a 22-minute time loop which resets every time the sun goes through a supernova and destroys the planet. This note was about how the poster wanted to get a tattoo memorialising the game. In response, another wrote: “I plan to get ‘Be curious on your journey!’ My favourite quote and a good reminder in life.”

These users are discussing the important messages within the stories of video games, the ways they connect to those stories, and how they carry them forward with them even when they are no longer holding a controller. Stories can be incredibly meaningful, and have a long-lasting impression on players.

In this way, the stories of video games can become far more than “just” stories (if such a thing even exists). They become incredibly meaningful narratives defining an individual’s life for themselves, and are often still thought about far after the moment of playing. These players see something important in the story – they see a meaning for the details in life, the reasons to keep going, and a way to view the world with new and fresh eyes.

As a piece of my Masters research, I spent some time talking to players of the Legend of Zelda series. The games vary in their approach to storytelling, with some being more streamlined and linear than others, but almost always with a similar retelling of the same hero narrative the player plays out. The symbol of the Triforce, three triangles arranged around themselves to form a fourth larger triangle, has come to symbolise the games themselves, but also has a place in the mythology of the gameworld.

According to the mythology of the Legend of Zelda, primarily set out by the 1998 release Ocarina of Time, the world was created by three goddesses. Once their labours finished, the three goddesses departed for the heavens. Three golden sacred triangles remained at the point where the goddesses left the world. These three triangles are the Triforce, and became the basis of Hyrule’s destiny and religion, and the place where the triangles rest became the Sacred Realm - a place away from place.

The story of the Triforce underpins the religious mythology of the world of Hyrule, the kingdom in the games. But the Triforce in this gameworld is not just a symbol, it’s a physical object which literally exists for the characters. It is said a person of equal parts wisdom, power and courage can touch the Triforce and get any wish granted. However, if someone does not have equal balance, the Triforce breaks, and its individual pieces come to rest with individuals who embody each of the three qualities.

While I was studying the series and its fans, I met someone who had a tattoo of the Triforce on their inner wrist. My participant repeated the elements of the story of the Triforce in our interview when I asked about it, and they commented on how they liked having the image in such easy view for them. Whenever they encountered a problem in life, or a tough decision, they said they liked being reminded of how they should approach life through a balanced approach of wisdom, power and courage.

This clearly shows an important aspect of storytelling in video games - these stories impact the individuals who play them. I don’t think carrying the important messages in stories is unique to video games, but it’s definitely present for the medium - the act of playing itself helps to cement these messages in a unique way.

As I mentioned before, video games are a special kind of storytelling which keeps its storied progression away from view unless the player is of a particular skill level. This isn’t exactly common in storytelling. When I read a fiction novel, I’m not quizzed on my understanding part way through, or required to have an understanding of what I would do if I were Elizabeth before I’m allowed to see the ending of Pride and Prejudice.

The Legend of Zelda, along with many other video games, however, does close off progression and story unless the player is capable of accessing the story. The direct act of playing the game, not just hearing the story, has a large impact on the way game narratives are experienced by players.

When Bioshock: Infinite was released in 2013, this activity was put to the direct test. The action-adventure game, which includes a lot of commentary on religion - particularly Protestant Christianity - opens with a scene of a baptism. The player moves the protagonist Booker DeWitt, who is sent to an airborne city that is a steampunk variation of the 1910s, portraying a particular view of American exceptionalism. In order to gain access to this city, Booker DeWitt must get baptised in the following of proclaimed prophet Zachary Hale Comstock.

The opening of the game involves the player moving through a landscape which appears much like a Christian church, with stained glass windows, soft choir music, and beautifully carved statues. There are candles everywhere, and a sense of spirituality is inherently present. As the player comes up to the baptism, in order to gain access to the city and therefore the rest of the game, the player must hit a button to accept the baptism.

This is where controversy struck. As one player told gaming outlet Kotaku: “As baptism of the Holy Spirit is at the centre of Christianity - of which I am a devout believer - I am basically being forced to make a choice between committing extreme blasphemy by my actions in choosing to accept this ‘choice’ or forced to quit playing the game before it even really starts.”2

The argument made was that if the opening scene had been entirely a cutscene, and the player simply watched this baptism happen, that would be one thing. But the act of pressing the button to accept the baptism was the equivalent of an act of blasphemy for these players. In other words, the active nature of the game, the requirement on player direct interaction, has such an impact on the experience of a game that some players felt they could not continue.

Therefore, we see how the interaction creates narratives for players is not always necessarily a positive for the players. In all these instances, those of Outer Wilds, Legend of Zelda, and of Bioshock, one thing is made clear - game narratives are massively impactful, and can directly affect the way the player thinks about their life far after the controller is put down. They are stories, absolutely, and the lingering affect they carry also makes them so much more than “just” stories.

The Grand Story of Life

Video games are massively important storytelling mediums in our contemporary society. Its story and meaningfulness are obvious to all who play them. Their role as art, game, and narrative all simultaneously is what makes them so massively interesting. That, and how the player interaction is so necessary to the medium as to define it.

Video games are stories: stories played, listened to, and experienced. They are stories we hear through the game itself, but they are also stories we spin to ourselves and to our loved ones. And they are so much more than simple stories, they are impactful stories, stories which change us and challenge us.

There’s a reason why when I think about my life, I think about the games I have played. There’s a reason why I think about Tetris when I think of my younger sibling, or how I recall playing music with my sisters inspired by the games we’d play. There’s a reason I feel so connected to games as to build an autobiography around them - it’s their stories. Their stories have become entwined with my stories, forming an inherent connection of togetherness. They are my cultural narratives, my social narratives, and my personal narratives.

1 For more on this, you can look at Frasca, Gonzalo. ‘Ludologists Love Stories, Too: Notes from a Debate That Never Took Place’, 2003. http://www.ludology.org/articles/Frasca_LevelUp2003.pdf and Murray, Janet. ‘The Last Word on Ludology v Narratology in Game Studies’. Vancouver, Canada, 2005.

2 Hernandez, Patricia. ‘Some Don’t Like BioShock’s Forced Baptism. Enough to Ask for a Refund.’ Kotaku, 16 April 2013. https://kotaku.com/some-dont-like-bioshocks-forced-baptism-enough-to-as-473178476.