The Taylor Swift Mythos

Alright, I know there’s a lot of discourse on Taylor Swift at the moment, which has been a combination of fascinating (as a researcher) and a little confusing. But I won’t actually be wading into that circle yet, because I feel that simply reflecting on how people come to specific beliefs needs more time, and quite frankly, the ability to look back with hindsight.

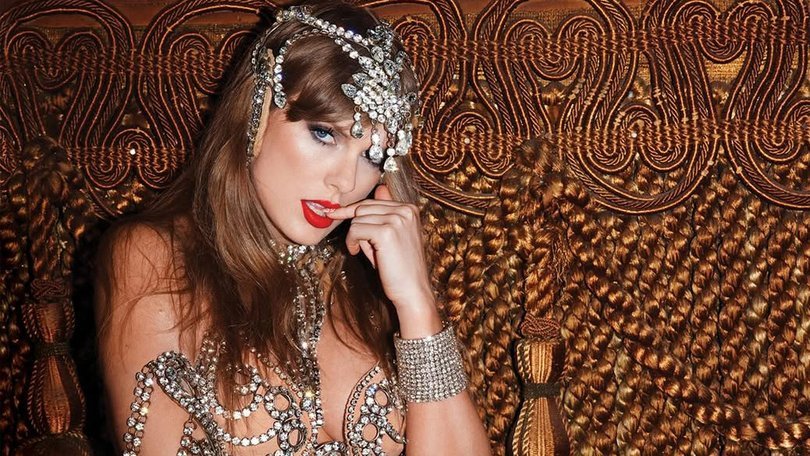

That being said, there is something I can speak to, and that’s the power and influence of Taylor Swift specifically. For some of those who have been arguing fiercely against her in the last few weeks, the simple act of constantly being fed Taylor Swift music and news is annoying. It’s hard to exist in this life without being exposed to her or her music. In fact, this sheer fact of her as a powerhouse of a contemporary pop figure is the point of my recent research into Taylor Swift: Taylor Swift is a mythic figure.

There’s a lot about this statement that can be broken down, but we’re going to start with an initial understanding of how her songs and her work as a complex of myths, or a larger mythos.

Mythology and Swift

Let’s start with my definition of myth. Like most things the realm of discussing people, there are a lot of choices when it comes to this, and some of you may be thinking this is a bit of moot point - we all know what a myth is. But… do we? We often use the word colloquially to mention something as being inherently false. Something being deemed a “myth” is akin to saying it’s not real, not true, and might as well just be ignored. But is that the way we think of mythology? Probably. A lot of contemporary readers may pick up the Prose Edda or the Odyssey and think it as some lighthearted fiction. But, what is often forgotten, is that there were - and actually still are - quite a lot of people who still believe fiercely in these stories.

Often, this idea of myth as being something inherently false is a flip of what has often been understood as the definition of myth from some early anthropologists and even some contemporary folklorists - myth is something which communicates truth. Something which speaks to a truth of the world is a myth, like why there’s thunder or what rain is. These explanations serve as forms of truth, explanations for how the world works. Because of that, some scholars, like E.B Tylor for example, considered that myth, and religion as well, would eventually die out with the continual embrace of science.

However, we can see in a multitude of religions, that an embrace of science does not necessitate an ebbing of belief. Islam, for example, was home to some of the earliest and most prolific scientists, including the first anthropologist. A lot of non-Christian beliefs see no need to throw out science or religion in favour of the other.

I am, of course, getting a little off track here. I’ve written about other definitions and approaches to the definition of myth in other places, and may do so again here on Substack, but maybe later. For now, let’s establish one thing for certain: what my definition of mythology is. For me, a myth is a narrative, or something akin to a narrative, that an individual or a community uses to understand themselves or the world around them.

Is this definition a little broad? Probably, though I find breadth just means there are fewer chances to accidentally bar someone out from a conversation who really does belong there. But, again, I’ll leave that discussion for a different place at a different time.

So, if a myth is a narrative people use to understand the world, then a complex mythos would be an interlacing of a multitude of different myths all layered on top of one another. In a past life, I wrote about the Slender Man mythos, using this terminology in order to best capture the interlacing narratives that make up his stories.

The next question, then, is pretty obvious: are Taylor Swift’s songs mythology? Well, it doesn’t take doing any kind of detailed study of my survey responses to know the answer is a resounding yes. Fans of her music, and even just people who listen without an intense Swiftie love in their heart, do feel a kinship to her songs. And before you start angrily typing some kind of response to me, I don’t think she’s the only musical artist who creates what I would define as mythology. One of the powerful things about music, and art more generally, is its ability to connect people, to make them feel something, to remind them of a moment in their lives, or to re-frame their experiences in a way that suddenly makes a different kind of sense.

For Taylor Swift, I have seen, read, and heard a variety of these stories from people who readily listen to her music. Some have talked about how her album the Tortured Poets Department has helped them through massive heartbreaking breakups. One listener said she and her son sing “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived” together as a way of coping with her child’s father’s abandonment of both of them. Many many listeners have talked openly about how “Bigger Than The Whole Sky” has helped them re-frame their experiences of miscarriage. Taylor Swift’s song has given them the ability to understand, re-frame, and connect to others through a shared experience of a strange grief that is often hidden and silenced.

And, yes, some of this is happening on her new album Life of a Showgirl. I watched Ally Sheehan’s reaction to the album, and her reaction to “Eldest Daughter” as a beautiful way to capture her very specific experience of being an online personality in the public eye, and the difficulty that comes with wading through inherently horrible comments.

Interweaving of Her Stories

Taylor Swift’s songs have some multitudes of meanings and interactions. It has become a fun pastime for some Swifties to engage in detailed analysis of the songs. The point of these endeavours is to uncover deeper meanings and connections throughout the album, as well as sometimes linking the album to other albums (more on that soon). If you want some details of this, Ally Sheehan, again, is a very good example of this.

When Life of a Showgirl first released, I found myself swimming through a multitude of posts, thoughts, and considerations about it, most of which was an exercise in “what was this song about?” or, often more importantly, “who?” This was also something which took up a lot of the discourse on her previous album the Tortured Poets Department.

So, there’s a double aspect of interpretation happening with Taylor Swift’s songs. There’s the level in which listeners engage with it as it appeals to them, and then also how it relates back to Taylor herself.

The process of finding Easter Eggs has become a hallmark of the Swiftie fandom. In 2021, Taylor explained that Easter Eggs started as a way to incentivise her fans to read the lyrics, but has since become a tradition and something she was immensely proud of. A lot of the ways Taylor Swift engages with her audience in their study of the lyrics can be explained through intertextuality and intratextuality.

The Intratextuality of Swift can be defined by comparisons, motifs, and imagery used throughout an album. Intertextuality, by contrast, is in how new texts re-imagine, relate to, or appropriate previous albums. In essence, Taylor uses intratextuality to connect the songs together within one album, and intertextuality to connect the songs throughout her entire career.

An example of intratextuality would be the repeated motif of going crazy in love in 1989. On the same album, we also have repeated imagery, such as red lips and flowers. But intratextuality becomes used when other albums return to this imagery, such as her revisiting a lot of these same images and themes in her song “Maroon” on Midnights.

Taylor Swift also actively uses what’s called “extratextuality”, which is when a work references work outside of itself, such as when she references The Rime of the Ancient Mariner or Peter Pan. Though, I’m going to return to this topic in a post at a different time.

This all means that Taylor Swift thinks about her albums as full pieces of work in themselves, and also think about how her discography all works together. Actively, we have a single song working as a myth, a larger album as a complex making a mythology, and her discography creating a larger complex of these mythologies - a mythos.

Looking Forward To More

But this is still a little too simple, because, ultimately, there is an inherently important piece of this mythological cog that we haven’t discussed yet - Taylor herself. As we’ve seen in the last few weeks, she’s a figure that encourages a lot of discourse, both related to and separate from her music. She has become a symbol, a figurehead, a stand-in for many bigger conversations. And this happens on both sides of the debate.

Taylor Swift as a person is fading into the myths she creates. She is not just someone telling you about Odysseus, she is Homer. And like Homer, she has become also a figure of mystery, commentary, and conjecture.

But that’s all for a different time, a piece of a larger mechanism. Like her stories, she is subject to Easter Egg hunting, textual analysis, and detailed analytical study. She also is a myth.

Anyway, I hope this helps to paint a better picture that these conversations currently being had are not simple, but neither is the subject of my study. If it was so simple, it probably wouldn’t be nearly half as interesting.